Gifs

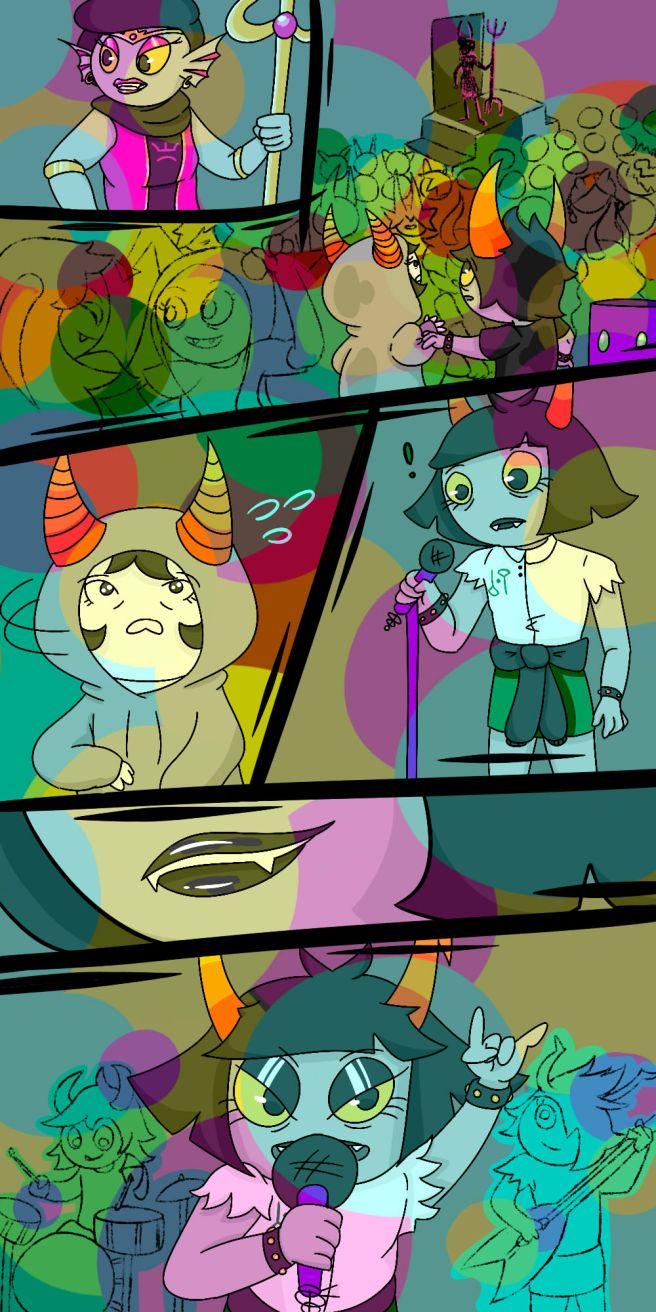

I’ve been trying to draw a little bit each day, so, to keep myself on that kick, I’ve been drawing and making gifs of the trollsonas of my friends and family.

A handful of digital images.

The first two were made for individual projects. The last was a background I made for a friends’ website.

Molt (2017)

![final 2 {"source":"editor","contains_fte_sticker":false,"effects_tried":0,"photos_added":0,"origin":"gallery","total_effects_actions":0,"total_editor_time":454,"tools_used":{"tilt_shift":0,"resize":0,"adjust":0,"curves":0,"motion":0,"perspective":0,"clone":0,"crop":0,"enhance":0,"selection":0,"free_crop":0,"flip_rotate":0,"shape_crop":0,"stretch":0},"total_draw_actions":0,"total_editor_actions":{"border":0,"frame":0,"mask":0,"lensflare":0,"clipart":0,"text":0,"square_fit":0,"shape_mask":0,"callout":0},"brushes_used":0,"total_draw_time":0,"effects_applied":0,"uid":"042C7D2F-D90C-4EBD-A6E9-4A2F5A76D3AF_1494305838918","total_effects_time":0,"sources":[],"layers_used":0,"width":2580,"height":3249,"subsource":"done_button"}](https://i0.wp.com/merrygoroundaboutcom.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/final-2.jpg?w=326&h=409&ssl=1)

These are two pieces I made by painting on canvas with acrylics and than digitally altering them. They combine the world of traditional art with modern/digital art. Art is limitless and there’s always new ways being found to create it.

The Future of Narratives

As The Digital Age continues to show an increase in digital narratives that combine various medias and aspects of the humanities, there is also an increase in people who possess reservations regarding these new narrative formats. However, these reservations have been around for almost as long as narratives themselves have as humans have transitioned from oral tradition to pictography to the written word and finally into hybrid narratives such as comics. As more narratives begin to emerge that combine different aspects of storytelling, it is important that both readers and authors keep an open mind when discussing the evolution of narratives because as they progress into digital formats they will help to create more immersive, poignant, and entertaining stories.

To understand where narratives are headed, it is important to know where they have originated from. The oldest form of storytelling that humans were capable of was an oral tradition. Oral storytelling is the creation of narratives through verbal language with the aid of expressions or gestures. Humans, once being nomadic, would travel to and fro, bringing with them legends, myths, and folklores. Spread through word of mouth around campfires, these tales would find their way into other groups and the tales would be retold, sometimes with variations to fit the land’s history so natives of the receiving region could better relate (Foley). Such an example would be “Cinderella.” Most are familiar with the western adaption, but very little realize that the story can be traced back to China and then even further to Ancient Greece (“Cinderella”). A more modern Chinese adaption of “Cinderella”, “Bound” by Donna Jo Napoli, incorporates the period of time where women in China were binding their feet for a beauty ideal, reinventing the narrative by personalizing it with the country’s history.

From the oral tradition, narratives then transitioned into pictography or, narratives told in the form of images such as cave drawings. In the Leang Timpuseng cave in Indonesia lies the very first “picture” created by man. Dating back 35,400 years ago is the image of a pig-deer. “This curly-tailed creature is our closest link yet to the moment when the human mind, with its unique capacity for imagination and symbolism, switched on” (Mott). With the creation of images, comes a higher level of thinking. Symbolism is born. Language is useful for communicating but if “[you] find early paintings, particularly figurative representations like animals… you’ve found evidence for the modern human mind” (Mott).

Progressing from pictography to written language, there is an in-between stage referred to as proto-writing. Forms of written language that mostly consist of images such as cuneiform and hieroglyphics, which date back to around the 31st and 32nd centuries, emerged. Based on the evidence that archeologists were able to gather, most examples of cuneiform are from traders, buyers, and sellers, indicating the first literate humans were actually accountants (Gascoigne). However, the very first recorded narrative was also found to be written in cuneiform. “The Epic of Gilgamesh” dates back to Ancient Mesopotamia around 2100-1800 BC and is considered to be the oldest preserved work of literature (“Gilgamesh: The First Epic”).

After this time period, written language became a popular and scholarly mode of storytelling. Poems and epics were popular means of narrative, as most were structured and well disciplined. A lot of these texts from Ancient Greece especially have even been preserved and retold in schools to this day. “The Odyssey” and “The Iliad” to name two. Then, in the early 20th century Murasaki Shikibu, a noblewoman from Japan, wrote the world’s first novel, “The Tale of Genji” in hiragana, a syllabic writing system developed in Japan (“Q. Who wrote the first novel in the world, and what was it about?”).

The leap from oral to written storytelling changed how narratives were viewed. Because oral tradition made it easy to create different versions by retelling the tales over and over it was thought to be more of a group effort. Each piece was collaborative and each story was part of the shared human experience. When the written word emerged, it allowed the author to maintain authority and ownership over the narratives they crafted. Stories became less collaborative and more about the individual. Whether a person believes this to be a bad or good change is relative. Textual storytelling might leave less up to interpretation but today modern readers believe reading text allows them to create their own ideas in their heads. However, many readers are still similarly disheartened by the leap into comics and then again into digital formats because they believe it takes away from their imaginative process when in actuality it merely is doing what the leap from oral to written storytelling did for ancient authors; it’s giving them more authority over their own stories.

The history of comics is one that is not well known, nor is it studied enough. Even attempting to research the first instance of a narrative that combines text with imagery is almost impossible because there are no articles pertaining to it. Therefore, it is difficult to say when humans first started mixing mediums. A good guess might be iconography or, pictorial illustrations associated with people or subjects, placed next to religious scripture.

But, more commonly, when a person is asked to think of the first story told deliberately with both images and text, children’s picture books are the first to come to mind. In 1658 “Orbis Pictus”, translated from Latin to mean “Pictures of The World” by John Amos Comenius became the earliest illustrated book specifically for children and was meant to be an encyclopedia (“The First Children’s Picture Book, 1658’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus.”). Following it less than a century later, in 1744 “A Little Pretty Pocket-Book” by John Newbery was published as the earliest illustrated storybook made for entertainment purposes (“A Pretty Little Pocket Book.”).

Running parallel to this, in the early 1700s came the works of William Hogarth, the man who was to be a precursor to political cartoons and comic-strips with his depictions of satirical paintings and caricatures (“William Hogarth.”). However, Rodolphe Töpffer, who’s works appeared in the 1800s is credited with being the father of the modern “comic”, with the first illustrated narrative being “Histoire de M. Vieux Bois” in 1827 published in English as, The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck (Kunzle).

The 1900s is when comics began to rise in popularity. The Sunday Strips in newspapers were becoming more common and by the mid-1900s full books dedicated to a particular comic were being published, referred to as “comic books”. This time period is referred to by comic fans as The Golden Age. In the 1930s Superman was created and other superheroes followed. In the 1940s when superheroes were no longer the craze, more genres of comics started being released, most notably, the mystery or detective genre (Ramsey). Comics were even considered effective enough as modes of storytelling to be used to calm young reader’s fears of nuclear war and atomic power after WWII when a comic book called “Dagwood Splits the Atom” used characters from the comic strip Blondie to explain the situation and the science behind atoms (Lockefeer).

And yet, there are still reservations about the change in mediums from text to comics and graphic novels. A lot of the literary community still considers comics to not be “fine art” or acceptable reading material. Comics are heavily perceived as sub-literature. But why? It could be speculated that because comics are a hybrid of both text and images that they are not dedicated to one aspect of the humanities (Christiansen, 1) . However, films, which also started gaining traction around the same time as comics, the first being “Roundhay Garden Scene” 1878, a short film directed by Louis Le Prince, are also not dedicated to strictly one aspect of the humanities and are held in much higher regard than comics (“Roundhay Garden Scene (1888)”). Comics are the combination of text and images and film is usually the combination of images and audio, but the differences in the hybridization of these two narrative senses does not seem to be the complete cause of why film is researched more than comics. There are also historical roots which associates comics with the satirical elements of political caricature and the naiveté of children’s literature which contribute to literary scholar’s inability to take comics seriously.

Despite these reservations to hybrid media even now, in The Information Age, the future of narratives continues to expand through the use of digital means. The future of narratives is digital, with increased hybridization of medias and platforms for story sharing. Combination narratives, or hybrid narratives, such as comics and films are becoming even more popular by merging the four senses of narrative in new innovative ways. These senses are text, visuals, audio, and intractability, which aligns with touch. (I’ve left out smell because despite the attempts of Smell-O-Vision in the 1960s and the implementation of some 4D movies, this sense has not risen to popularity, nor is it still being commonly used today (Fletcher).) Some examples of these combination narratives implemented through digital means would be podcasts, webcomics, videos, animation, social media platforms, and video games.

To date, the most advanced piece of narrative, in that, it uses as many combinations of the senses of narrative as possible to tell its story, is the webcomic “Homestuck” by Andrew Hussie. It includes flash animations, flash games, gifs, still images, long walls of text, and some of the characters also have social media accounts from platform sites such as DeviantArt, Instagram, and Snapchat. Its ability to touch upon all of its audience’s senses makes it an immersive experience, easily able to pull its readers in (Hussie).

But, much like there were those reluctant to watch the leap from oral to written and written to hybrid narratives like comics, so too are people now reluctant to follow narratives into The Digital Age. Some particular issues authors and readers have with digital storytelling are publication complications, or ownership of posted/published materials, censorship, or who is allowed to view restricted content, and the digital divide and the generation gap, where many people in the literary community believe they cannot access digital storytelling, either because they do not understand the means to use it or they are now out of touch with what the younger generation is recounting online.

But digital storytelling is not meant to hinder or limit readers as much as it is meant to appeal to all of their senses, and, for some this can be overwhelming at first. However, in the long run it creates a more entertaining reading experience. Even stories regarded as classics are being retold with digital narratives, having life breathed back into them. “The Metamorphosis” by Franz Kafka was recently reinvented by comic illustrator Peter Kuper. Kuper uses text from the original story, imagery from his comics, audio in the form of tension creating music, and intractability as the reader clicks and reads through some background information regarding both Kafka and Kuper. There are even reviews available that state: “Acclaimed graphic artist Peter Kuper presents a brilliant, darkly comic reimagining of Kafka’s classic tale of family, alienation, and a giant bug. Kuper’s electric drawings—which merge American cartooning with German expressionism—bring Kafka’s prose to vivid life, reviving the original story’s humor and poignancy in a way that will surprise and delight readers of Kafka and graphic novels alike” (Kuper). There is an appeal here for more than one audience. Older generations and literature lovers will like it because it “reviv[ed] the original story”. The younger generation will like it because its format appeals to more than one sense. And the author is proud of it because: “Peter Kuper’s fascination with entomology began at the age of five but was supplanted by his discovery of comic books several years later. Thanks to Franz Kafka, Kuper no longer has to choose between the two. His comics and illustrations appear regularly in numerous magazines and newspapers, including Mad, for which he draws Spy vs Spy every month. Give It Up!, his first collection of Kafka adaptations, was published in 1995” (Kuper). The key phrase is “[he] no longer has to choose between the two”. Hybrid narratives have allowed Kuper to continue expressing himself artistically in any way he wishes.

And, with this expression, he displays just how mixing mediums add to a narrative. By engaging with more than one sense, a narrative becomes increasingly immersive. There is also the positive aspect that, by a story being accessible through more than one sense, those that might lack a sense are able to engage with the narrative as well, an example being audio books for those who are visually impaired. Like Kuper, the author is also given more control over what narrative they are choosing to present and how they choose to present it. And, although the author is given more control, rather than limit audience interpretation, it becomes heightened, as there are now multiple aspects of the narrative to interpret such as how the music from Kuper’s retelling of The Metamorphosis and the way Gregor was shown tossing and turning in bed in his relentless struggle to flip over created more tension and horror than just reading the original Kafka text alone: “That was something he was unable to do because he was used to sleeping on his right, and in his present state couldn’t get into that position. However hard he threw himself onto his right, he always rolled back to where he was. He must have tried it a hundred times, shut his eyes so that he wouldn’t have to look at the floundering legs, and only stopped when he began to feel a mild, dull pain there that he had never felt before” (Kafka). Text alone does not always have the same effect as narratives told in digital formats. If a person reads Kafka’s text they might feel their heart beat a little faster, but experiencing the part in Kuper’s retelling, there is a distinct heartbeat noise already playing just beneath the surface of the eerie music, guaranteed to make the audience of its narrative feel more immersed in the tale (Kuper).

The art also contributes to how the story is perceived. Told in black and white, the comic aspect is horrific and colorless, dull and miserable just like Gregor’s life as a door-to-door salesman. “’Oh, God”, he thought, ‘what a strenuous career it is that I’ve chosen! Travelling day in and day out. Doing business like this takes much more effort than doing your own business at home, and on top of that there’s the curse of travelling, worries about making train connections, bad and irregular food, contact with different people all the time so that you can never get to know anyone or become friendly with them. It can all go to Hell!’” (Kafka). The almost realistic but still comic-style black and white images also help the story set its tone as one of seriousness, misery, and strife. Just like this, these added elements of both audio and sound allow for a greater range of narrative analysis.

With the progression of the narrative from oral all the way to The Digital Age, digital and hybrid narratives should not be as contested as they are. Despite the human tendency for innovative change and the contradictory and almost fearful reluctance of change narratives will continue to evolve and create works that are more immersive and appeal to as many different senses as authors can imagine and create. There is definitely not enough research being done in the field of the digital humanities and on how narratives are evolving but by accepting new formats for narratives, authors will maintain greater authority over their pieces and readers will have more than just text to enjoy and be entertained by. The mingling of the many different aspects of the humanities should be a celebrated topic rather than something to be resented. Much like how Peter Kuper has given a new life to Franz Kafka’s tale The Metamorphosis, other innovative hybrid narratives will continue to be created, enjoined, and perhaps one day even studied by future readers and literature lovers.

Work Cited

“A Pretty Little Pocket Book.” The British Library. The British Library, 06 Feb. 2014. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/a-pretty-little-pocket-book>.

“Cinderella.” Cinderella – New World Encyclopedia. N.p., 22 Feb. 2017. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cinderella>.

Fletcher, Dan. “The 50 Worst Inventions.” Time. Time Inc., 27 May 2010. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1991915_1991909_1991849,00.html>.

Christiansen, Hans-Christian, and Anne Magnussen. Comics & Culture: Analytical and Theoretical Approaches to Comics. Copenhagen: Museum Tuscalanum Press, n.d. Print.

Foley, John Miles. “Oral tradition.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 12 Sept. 2013. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.britannica.com/topic/oral-tradition>.

Gascoigne, Bamber. “History of Writing” HistoryWorld. From 2001, ongoing. <http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?historyid=ab33>

“Gilgamesh: The First Epic.” The Epic of Gilgamesh. University of Idaho, n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://webpages.uidaho.edu/engl257/Ancient/epic_of_gilgamesh.htm>.

Hussie, Andrew. “Homestuck.” MS Paint Adventures. Andrew Hussie, 13 Apr. 2009. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.mspaintadventures.com/>.

“The First Children’s Picture Book, 1658’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus.” Open Culture. N.p., 22 May 2014. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.openculture.com/2014/05/first-childrens-picture-book-1658s-orbis-sensualium-pictus.html>

Kafka, Franz. “The Metamorphosis.” Gutenburg. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5200/5200-h/5200-h.htm>.

Kunzle, David. “Father of the Comic Strip Rodolphe Töpffer.” University Press of Mississippi. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.upress.state.ms.us/book>

Kuper, Peter. “Franz Kakfa’s The Metamophosis by Peter Kuper.” Franz Kafka’s THE METAMORPHOSIS adapted by Peter Kuper. N.p., Aug. 2003. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.randomhouse.com/crown/metamorphosis/>.

Lockefeer, Wilm. “Dagwood splits the atom.” The Ephemerist. N.p., 22 Apr. 2008. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.sparehed.com/2007/05/14/dagwood-splits-the-atom/>. s/869>.

Mott, Jo Marchant Justin. “A Journey to the Oldest Cave Paintings in the World.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, 01 Jan. 2016. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/jo>

“Q. Who wrote the first novel in the world, and what was it about?” First Novel – Language – Explore Japan – Kids Web Japan – Web Japan. Kids Web Japan, n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://web-japan.org/kidsweb/explore/language/q1.html>. urney-oldest-cave-paintings-world-180957685/>.

Ramsey, Taylor. “The History of Comics: Decade by decade.” The Artifice. N.p., 5 Feb. 2013. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://the-artifice.com/history-of-comics/>.

“Roundhay Garden Scene (1888).” IMDb. IMDb.com, n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0392728/>.

“William Hogarth.” The National Gallery. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/william-hogarth>.

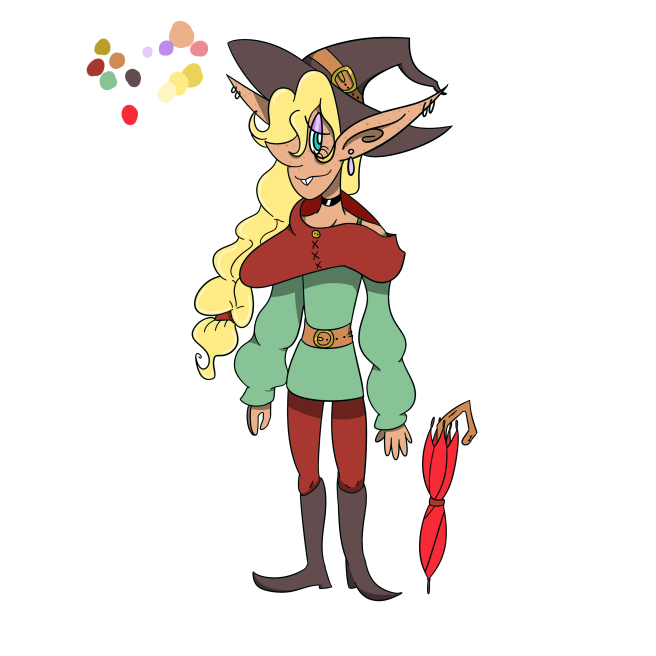

I decided to redo my Taako design. I wanted something with lighter colors and a style that’s simple but cartoony. I might dabble in animating him a bit later so I think this design will be easier to use.

I decided to redo my Taako design. I wanted something with lighter colors and a style that’s simple but cartoony. I might dabble in animating him a bit later so I think this design will be easier to use.

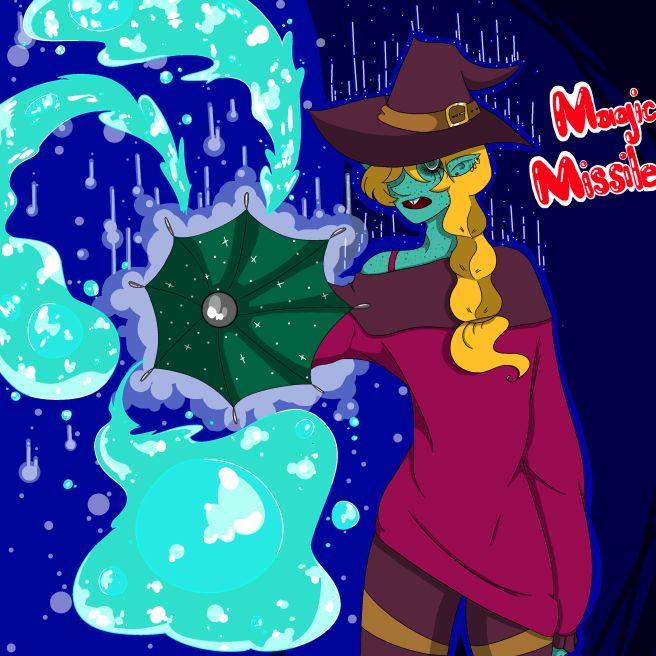

Magic Missile

Some more “The Adventure Zone” art of Taako. I have just been obsessed with this lately. And, of course, Taako is my favorite.

Magikarp Jump Trainer

I’ve been into this game like BIG TIME. I’m already rank 75.

D&D Character

I’ll be posting some stand alone drawings I’ve been doing and the first is my D&D character Calypso Mossswallow. She’s a Drow Ranger with the Chaotic Good alignment and her whole development is centered around fighting her Drow nature (since Drow are usually CE or CN) with nurture or the way she was brought up (She was raised by human parents.). She left her adopted family when she found out that they were losing business for raising a Drow child.